I have written a fair amount in various publications about the effect of Norfolk and its coast on our most illustrious writers. Possibly the greatest of the Sherlock Holmes stories, ‘The Hound of the Baskervilles’, was inspired by events at Cromer; Charles Dickens took to the area, enthusiastically featuring it in ‘David Copperfield’; Black Beauty by Anna Sewell was written in Norwich and has since sold over 50 million copies. Here is a peek at Rupert Brooke and his relationship with Cley Next the Sea.

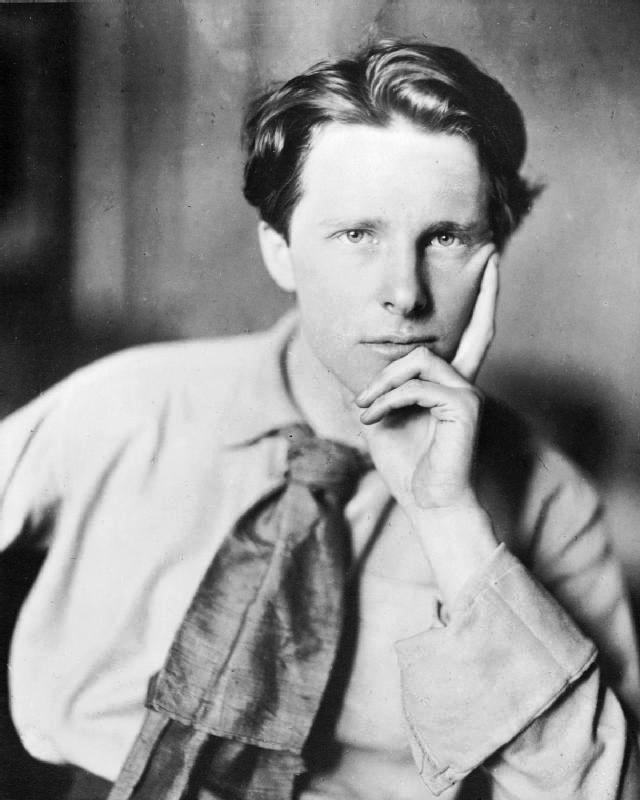

‘He was a minor celebrity before he died and a monstrous one afterward, holding on, to this day, to his fame and a rather tattered glory’ The New Yorker, in an article dated April 23 2015, the hundredth anniversary of his death .

The poet Rupert Chawner Brooke was staying at Cley on the Norfolk coast when he heard of the outbreak of war. Frances Cornford, granddaughter of Charles Darwin, was with him at the time and wrote:

‘A young Apollo, golden-haired,

Stands dreaming on the verge of strife,

Magnificently unprepared

For the long littleness of life’.

He reputedly did not speak for a day until Frances Cornford asked: ‘But Rupert, you won’t have to fight?’ to which he replied ‘We shall all have to fight’.

W.B. Yeats called him ‘the handsomest young man in England’ and he had an illustrious group of friends. He joined the navy and, following his death on April 23 1915 when his unit was sailing to Gallipoli, Winston Churchill wrote that he ‘was all that one would wish England’s noblest sons to be in the days when no sacrifice but the most precious is acceptable’. He died on 23 April on board a hospital ship moored off the Greek island of Skyros and was buried in an olive grove there later the same day as his unit was in a hurry to leave. He had been bitten by a mosquito and passed away from blood poisoning, although in his obituary Churchill claimed that he had died of sunstroke – an image to suit the times, one of a young English literary lion, dying in Greece like Byron. The well-known description by his friend, William Denis Browne, who sat with him to the last, of his end embellished the myth: Brooke passed away ‘with the sun shining all round his cabin, and the cool sea-breeze blowing through the door’.

Unlike his famous contemporaries Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, Rupert Brooke saw no fighting and he epitomized for many the youthful idealism and devotion to country felt during the first year of the war. In 1912 he had written The Old Vicarage, Granchester. He was in Berlin and longing for home and the poem presents a fervent, enchanted view of English rural life which caught the imagination of the period. It ends like this:

‘Oh, is the water sweet and cool,

Gentle and brown, above the pool?

And laughs the immortal river still

Under the mill, under the mill?

Say, is there Beauty yet to find?

And Certainty? And Quiet kind?

Deep meadows yet, for to forget

The lies, and truths, and pain? . . . oh! yet

Stands the Church clock at ten to three?

And is there honey still for tea?’

His patriotic sonnet The Soldier was read from the pulpit of St Paul’s Cathedral in April 1915.

‘If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware,

Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam,

A body of England’s, breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.

And think, this heart, all evil shed away,

A pulse in the eternal mind, no less

Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given;

Her sights and sounds; dreams happy as her day;

And laughter, learnt of friends; and gentleness,

In hearts at peace, under an English heaven’.

Legacy divided

Few poets have polarized thought so much. George Woodbury, in his introduction to Brooke’s Collected Poems (1916) wrote:

‘There is a grave in Scyros, amid the white and pinkish marble of the isle, the wild thyme and the poppies, near the green and blue waters. There Rupert Brooke was buried. Thither have gone the thoughts of his countrymen, and the hearts of the young especially. It will long be so. For a new star shines in the English heavens’.

Woodbury’s contemporary, poet Charles Sorley who was killed in 1915, had a rather more cynical view of all war poetry:

‘The voice of our poets and men of letters is finely trained and sweet to hear; it teems with sharp saws and rich sentiment: it is a marvel of delicate technique: it pleases, it flatters, it charms, it soothes: it is a living lie’.

Recently a bundle of papers has been opened by the British Library that details his love affair with the poet Phyllis Gardner and other loves.

There is a Rupert Brooke society based in Norwich at www.rupertbrooke.com

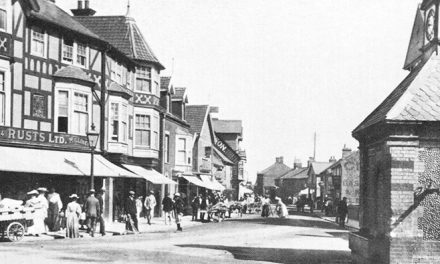

Cley today

Cley today earns its living from tourism. Apart from the famous windmill and church, it is a bird watching site of international importance, all the year round. Here you can see Grey Plovers, Black-tailed Godwits, Spoonbills and several types of waders.

It is also well known for smoked fish and meats. These go particularly well with the designer ales you can find in the pubs around here. Of particular fame is the ‘red herring’. If you are wondering what this is, it is a kipper that has been smoked for at least three weeks giving it a very, very strong taste which is not for the faint-hearted. However, sliced very thinly it can be perfect to have with a pint of fine ale.

Last century, Victorian villains hit upon the idea of throwing a few ‘red herrings’ onto the trail of pursuing police dogs as this completely covered up their own scent. Hence the saying in detective stories of a red herring being a wrong path to go down.

Modern day photography by Daniel Tink