COLOUR PHOTOGRAPHY DANIEL TINK

William the Conqueror managed it in 1066 but since then no foreign power has ever managed to invade these islands. There has been no shortage of attempts and plans from the Spanish Armada, to Napoleon, to Hitler but, by courage or fortuitous circumstance, the threat has never been carried out. However, there was a time 100 years ago when invasion was seen as highly likely and it was believed that the Norfolk Coast was where it would begin.

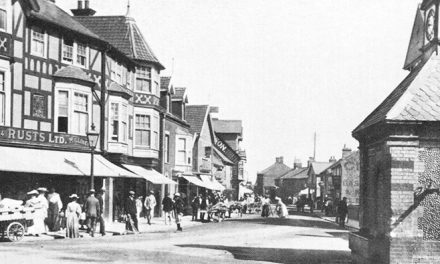

It is August 1914. Much like this summer it is very hot and a large section of Norfolk people has decamped to the seaside. Hotel bookings at Cromer and Sheringham are at record levels. Most did not believe that Great Britain would be affected by the events in Belgium, Germany and France or that we need be involved at all should fighting begin. However, on Tuesday 4th August the late night edition of the Eastern Daily Press announced that we were indeed at war.

The coast prepares

It was on the Norfolk coast that defensive measures were first introduced. Settlements such as Happisburgh and Weybourne were considered prime sites for a hostile landing as the sea here was deep enough to allow ships to closely approach the shoreline and land men and machines. Immediate action was taken to defend them. In Happisburgh, for example, a division of what were known as ‘Rough Riders’ – cavalry hastily drafted in from all over the country – were billeted in private houses. Trenches were dug along the cliff tops and the beaches shut to the public completely between sunset and sunrise: at all other times special permission needed to be obtained from the Lieutenant Colonel in charge of defences.

Many local women of coastal settlements were also formed into groups to make clothing and bandages for troops.

Fears of invasion

In 1914 there was a school of thought that saw invasion as highly likely. There were literally dozens of graphic full length novels published in the early 1900s giving no-holds-barred and horrifying accounts of life under a foreign conqueror. A best seller was William Le Quex’s The Invasion of 1910 which sold over a million copies. In this book, the Germans landed at Lowestoft. In another, Swoop of the Vulture, Lowestoft and Yarmouth were invaded helped by previously unknown German sympathisers. In another, the Japanese landed at Liverpool. Erskine Childers, a future war hero, even got into the act with his famous novel The Riddle of the Sands.

There was also what is known as the Blue Water School of thought which believed that as long as Britain commanded the seas there was no possibility of invasion. According to this theory, championed by the Admiralty, if Britain surrendered command of the seas, the army would be ineffective anyway in the case of a multiple assault. The enemy would land on the Norfolk coast or maybe south of Lowestoft and sweep into London. The sinking within 90 minutes of the Hogue, Aboukir and Cressy by a single German U-boat dealt the Navy a huge psychological blow, at least temporarily, and did little to reassure the concerns of people living on the coast.

The fishermen

Protection of the Norfolk coast relied not just on the British Navy but also on North Sea fishermen many of whom were enrolled in the Royal Naval Reserve Trawler Section. They were to use their own vessels in a variety of war work – patrolling, minesweeping and anti submarine operations. Some smacks, commanded by skippers such as Thomas Crisp and Charles Fryatt, whose heroic exploits have previously been featured in this magazine, played an active part as combatants and created instant legends which greatly helped morale. The Germans were under no illusions as to fishermen’s value and sank 26 boats within the first four weeks of hostilities. Over 500 herring drifters from Yarmouth and Lowestoft were hired by the Royal Navy during the course of the war. In addition, in 1914, four of the largest Yarmouth steam drifters were used to install heavy steel anti-submarine mesh in what was called the Swin anchorage off Maplin Sands. This proved a vital anchorage for battleships of the 3rd Battle Squadron.

At the beginning of the war German ships which happened to be in British ports were captured. The Fiducia was taken at Great Yarmouth and several at the major ports such as Kings Lynn and Ipswich.

Put those lights out!

The Eastern Daily Press ran this letter:

Sirs, In accordance with the Defence of the Realm Act, I hereby give notice that all lights on the coast of Norfolk showing to seaward from all buildings are to be screened from sunset to sunrise. Every person infringing this regulation will be liable to arrest. Also that any unauthorised person showing a light on the seashore (or on the cliffs adjoining thereto) will be liable to arrest. Any person signaling with any lamp or otherwise will be liable to be shot without further warning. I have the honour to be, Sir, your obedient servant. A.A .Ellison, Captain in Charge, Lowestoft and Yarmouth.

Anti-German feeling and spies

Germans in Britain were subject to suspicion, although the press in Norfolk said that relations between the county’s citizens and those of German nationality were more friendly than elsewhere. Some, however, believed that all Germans should not merely be registered but sent to an (unspecified) colony and a letter in the local paper suggested that anything reminding the good people of the county with anything Germanic, should be banned, including sausage dogs.

Many hotel and guest house owners found that those people who had registered for a holiday failed to show up. One high profile case involved a German guest house owner in Sheringham, Jacob Lichter, who brought a case against some guests who had failed to appear after war broke out. Judge Mulligan of North Walsham Crown County Court threw the case out adding some remarks about the absurdity of allowing Germans to own guest houses on the vulnerable coast.

Spies were everywhere, some believed. One such was the MP for Kings Lynn, Holcombe Ingleby, who believed that Zeppelins were being assisted by car owners who were using their headlights to signal from coastal roads. One man was arrested for sketching on Sheringham sea front. So febrile was the atmosphere that there were those who believed any light showing in a house on the coast had an ulterior purpose. Major Egbert Napier, Chief Constable of the Norfolk County Constabulary, spent much of his time hunting spies on the Norfolk coastline. He subsequently signed up for the Royal Garrison Artillery and was killed in October 1917.

The Diss Express for Fri Sept 11, 1914 carried this item, one of many showing the nervousness of some folk:

ENEMIES IN OUR MIDST

A large number of German and Austrian subjects liable to military service have been handed over to the military authorities… A few days ago there appeared in the press a circumstantial report of a midnight attack by two men on a signalman. On enquiry it was found that the signalman was suffering from nervous breakdown, and there was no truth in the story. There have been reports of attacks on police constables by armed motor-cyclists, but in no case was the report substantiated. Reports of the discovery of secret arsenals are untrue.

In early 1915, the Norfolk and Suffolk Journal, reported a successful prosecution: FLASHES TOWARDS THE SEA .Sentence of six months hard labour was passed at Spilsby, Lincs on Monday on Bertie Whydale, cycle repairer, for having, Feb 14 1915, contrary to the regulations made under the Defence of the Realm Act, displayed a light ‘in such a manner as could serve as a signal, guide or landmark’ …At 11.20 on the night of 14th ‘he was seen flashing an acetylene lamp from a hill, 250 feet above sea level towards the sea’.

Less selfish?

As the war progressed, the Bishop of Norwich saw an uplift in people’s ethics. He is reported in the Norfolk Chronicle of December 15 1915 as saying in an address entitled VICTORY AND REACTION: ‘I can foresee that the very time of victory itself will be a time of excitement and danger. There will then be the risk that our men may fall into easy paths. How dreadful once more to drop down into that flat, unimaginative, unentertaining life, petty, small, self-pleasing, self-seeking from which, through the war, we are now being raised to something better’.

Coastal defences: How they developed during the war

When the war began, the coast had no defences to speak of – except for warnings from the Coastguard and boy scouts, and the latter were quickly and enthusiastically organized to make patrols. Kings Lynn boasted a small battery and, right around the coast, Southwold had some old canons. Harwich, of course, being the major naval centre for the region, had fortifications, including searchlights and a minefield as well as some new 9.2 inch guns.

It was widely believed that, if Germans invaded, the fleet would cut them off and that the enemy would soon surrender in inhospitable territory with no supplies. Thus, in 1914, Essex, Norfolk and Suffolk had each only one Infantry Brigade, one mounted Yeomanry Brigade, a brigade of the Royal Field Artillery and two battalions of cyclists. Harwich had six battalions of infantry.

There was fevered discussion as to where the enemy was likely to land. The salt marshes at Weybourne were seen as unsuitable and the wide expanses of beaches between Cley and Sheringham, and possibly Lowestoft, were considered quite likely.

Home Defence, trenches and additional guns

Initially, much reporting was of an optimistic nature. The Norwich Mercury of December 9 1914 reported: A HOPEFUL OUTLOOK. The latest war news from the Western Front appears to show that the Germans have abandoned the attempt to force their way to the coast. In the same edition it reports on Home Defence: ‘the new volunteer movement which has sprung out of the possibilities of an attempt at an invasion of our shores grows in force day by day…Today there are upwards of a million men, aged from about 35 upwards…In our own area, Yarmouth has done well, with over 500 men already enrolled. Lowestoft has followed suit with 250 and Norwich has begun its task with over 400 men in the first few days of the appeal…’

The Authorities were not keen to dig up beaches in 1914 so as not to alarm public but eventually began to do so, including on Sheringham Golf Links. Also, by1915 there were six 4.7 inch guns moving on travelling carriages at Weybourne and two more at Cromer.

Harwich was made into strong fortress in 1914. In 1915 two 9.2 inch Mk X guns were brought from Ireland, the most powerful pieces ever to be put on the East Coast. They could fire a shell of 280 pounds up to 17,000 yards and reach any ship threatening the base and town.

In 1915 an armoured train was brought to Norfolk: it looked very impressive but was militarily useless as it was on fixed tracks and relied upon the enemy obligingly coming within range. Based in North Walsham, it comprised four carriages with a steel shell half an inch thick. At either end was a gun truck with a Maxim gun and 12 pounder naval gun. For the duration of the conflict it noisily banged up and down the track on the Mundesley line as far as Great Yarmouth and it never fired a shot.

Air threats led to two 75-mm guns being placed at Bacton and two more at Sandringham to protect the Queen. In addition the airbase at Pulham Market had 3 3-inch guns and Yarmouth two 18-pounders.

In 1916, following the April bombardment of Lowestoft by the High Seas Fleet, which caused great panic and fear on invasion, trenches were dug along the cliffs at Pakefield and inspected by the King.

If we are invaded, this is what we shall do

In 1916 it was decided by the Admiralty and War Office that an invasion by up to 160,000 men was quite possible and that half a million troops must always be stationed in the UK to counter the threat. The attack was deemed probable between the Wash and Dover. Consequently two command posts were set up, one at Bretford and one at Mundford. The defence plan was to hold the coast as long as possible and then, if German troops landed, seen as probable for exercise reasons, then they should be attacked by mobile units of cyclists and infantry. Thereafter it was pretty much harass and hopefully defeat the enemy on the way to London – it was assumed the enemy would make a beeline for the capital.

The government also sought the active help of the public in keeping vigilant. The Eastern Daily Press of Tuesday July 18, 1916 wrote: ‘The War Office request that the public will render assistance…by notifying…of any bomb or projectile or fragments thereof or any other article discharged, dropt or lost from any enemy aircraft or vessel’.

The defences never approached those of the Napoleonic wars but in 1917 more trenches were dug at Weybourne and Sheringham, Sea Palling and Great Yarmouth. South of Lowestoft was further strengthened by guns and men. Weybourne in particular became an important Army coastal defence base.

Mobile guns included six 60-pounders at Weybourne, Mundesley and Pakefield: these would be useful against troops but were not really designed to pierce armour. Cromer also had two of the same guns in a permanent mount. Monitors operated 24/7 from Lowestoft and Great Yarmouth.

Pillboxes

Some 48 pillboxes, named, some say, because of their shape which resembled the boxes that pills could be obtained in from the local chemist, were built in Norfolk, the majority along the Norfolk coast. The picture is not entirely clear, especially as some were re-used and adapted in the Second World War. 24 remain today.

Often circular or hexagonal in shape and made of concrete, they were designed to protect British troops when firing at the enemy through the ‘loopholes’. Steel shutters could cover the openings when in defensive mode. They were often built in pairs to provide greater support and they ran from Cley to West Runton. It is possible that the pillbox at Stiffkey was also in this defensive line but experts even now are trying to work out whether it was built in the First or Second World War. It is unsually flat, thus making it difficult for troops to stand inside and the openings are wider than normal: possibly it was some kind of observation, rather than defensive, post. A second line reinforced these and ran just inland between Holt and Aylmerton. A line ran along the banks of the River Ant with other locations including Mundesley, Bacton, Sea Palling Hanworth, North Walsham and Great Yarmouth. Many were built by the Royal Engineers.

The Pillbox Trail

A Pillbox Trail was launched with great success in 2015. 14 are accessible and these are: Stiffkey, Weybourne, Beeston Regis, Aylmerton, Thorpe Market (2), Bradfield, (2), Little London (2), White Horse Common (2), Wayford Bridge and Sea Palling. Further information and leaflets are available from any north Norfolk information centre or online. www.visitnorthnorfolk.co.uk