A brand new Sherlock Holmes tale

The Adventure of the East Cheam Retirement Home

Narrated By John H Watson MD

An agitated young man rushes into Dr Watson’s surgery but flees before the good doctor can question him as to what might be the trouble. He leaves behind a notebook encased in pale blue leather; there is nothing in it save a Latin inscription ‘Spectemur Agendo’. What is it that ails him and what is the significance of the notebook with its mysterious message? There is only one thing for Dr Watson to do: take it to the single man in London who may be able to cast light on the puzzle – the world’s first and only consulting detective, the famous Mr Sherlock Holmes.

TALES FROM MY SURGERY

In all the many cases I have tried to faithfully record concerning my adventures with my friend, Sherlock Holmes, there was several, as I recall, which began with me bringing the initial facts to his attention. One such was the Adventure of the Engineer’s Thumb, a case, like the one I am about to relate, that actually began in my surgery at Paddington.

I was not at this time, in the early months of 1892, living in our famous rooms at 221B Baker Street, having recently been blissfully married and now the proud owner of a medical practice not too far from my former abode. When in Mrs Hudson’s care at Baker Street, cases had come to us, more often than not, as a result of someone tugging the bell-string, and presenting Holmes with a set of mysterious facts that were sometimes interesting enough to gain his immediate attention. Often, however, especially as he became more and more famous, some of the ‘cases’ we heard in our cluttered sitting room were simply of insufficient interest to merit his energies and it fell to me to usher the crest-fallen would-be client down the stairs and out into the often inclement London fog. No amount of money was of consequence to Holmes in circumstances like this as he was prepared to act solely according to the interest a set of facts offered: indeed, sometimes he waived his fees altogether if the client did not have the wherewithal to pay and the case was original and taxing enough to challenge his legendary mental faculties. A case was especially magnetic to him if Scotland Yard had tried and failed to get to the bottom of it.

At times I thought he could be unsympathetic, even cruel when his interest was not aroused, such as after hearing the pathetic tale of the two lost twins of Shropshire or the sadly mysterious circumstances surrounding Lady Ethel Pomage’s bigamous marriage, a case I was forced to solve under my own steam as I felt so strongly for the poor lady, and which I may one day commit to paper. I thought his comment on seeing a report of my success in the Times somewhat sniffy, even jealous: ‘So you’ve solved one on your own, old chap. Well done – one of the simpler deductions, to be sure’. It did not help my fury nor ego when he added: ‘The culprit was, of course, the second gardener who turned out to be Lady Ethel’s long-lost son!’

‘Really, Holmes, if you knew it all along, then why did you not tell me?’

‘Boys must have their fun, my dear chap. Anyway, I wanted to see if you would get there in the end!’ Sometimes, I found the arrogance and insensitivity of the man almost insufferable. And yet there were times, many more of them, when I would gladly have done anything for him.

To his credit, he did, during the period under discussion, solve two of his most famous and unusual cases, the Adventure of the Speckled Band and the Adventure of the Five Orange Pips, in both of which I was proud to have been of some little service.

The adventure I am now about to relate began, according to my notes, in the spring of 1892 when the air was crisp and sweet with the promise of a fine summer to come. I had seen several clients in my Paddington surgery and was looking forward to my cherished morning tea break when, into my examination room and past my beloved wife who was at this time acting as my receptionist, rushed a very agitated young man of about eight and twenty. ‘Dr Watson, Oh Dr Watson, I am so sorry to trouble you, but you must see me…’

I looked at this well-dressed, obviously educated chap standing before my desk with my worried wife hovering behind, waiting, as we had so often discussed before, for my signal to call the police and have him removed. But I hesitated. He would have been handsome, with a shock of ginger hair and a moustache almost equal to my own (of which, I am, as my readers know, very proud), but for his truly pathetic countenance and the imploring look of a Springer Spaniel. He was dressed in a fine suit which was somewhat crumpled, his shirt showed signs of not having been changed for a day or more and his bright red and blue tie, which I recognized as belonging to the alumni of one of our great public schools, hung loosely down from his neck as if he had been clawing at it.

‘My dear Sir,’ I said, ‘please take a seat. You must tell me what ails you. I am in no hurry this morning, until such time as I have to visit my good friend Sherlock Holmes later …’

‘Ah, Sherlock Holmes, Sherlock Holmes, yes…Oh absolutely’, he half screamed, staring wide-eyed like a madman around my surgery.

I admit to alarm at this point. ‘My dear young man, before you have need of any medical services I may be able to provide, I think you have need of something more immediate and prosaic. I have some brandy in the adjoining room. Please wait here a moment and I shall fetch it!’

I quickly left the room, fetched the brandy bottle and two glasses, and returned. But when I entered the room, it was empty. I noticed that the French doors leading to the garden were wide open. Of my visitor and the preceding events there was no sign save one – on my desk was a leather-bound book of light blue colour. My wife, who had heard the commotion, rushed in and her gaze, too, fell on the volume. Tentatively she picked it up and flipped through it. ‘My dear, there is nothing in it at all. It appears to be brand new. Ah…hold on, written under today’s date there is something. What is it? Yes, it says ‘Spectemur Agendo. What on earth is that?’

‘It is Latin, my darling’, I said, summoning up my Grammar School Classical Studies. It means something like ‘Let us be judged by our actions’.

‘Judging by HIS actions, I would say he is one test-tube short of a full medical set! What are we to do? There’s little point in chasing him, is there? He will have got clean away out of our back gate by now.’

‘Well, that, anyhow, is easy. I am due to see Sherlock at noon. I shall take the book to him,’ I said, chuckling inside and more than a tad gratified to be able to take him another puzzle and so soon after the ‘Engineer’s Thumb’ case. ‘I think I might as well go immediately.’

My wife told me later that she was surprised, after all that had occurred, to see me leave shortly in fine spirits, apparently smiling to myself and quietly humming the chorus from La Boheme.

A CONSULTATION WITH HOLMES

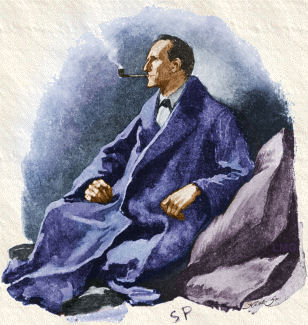

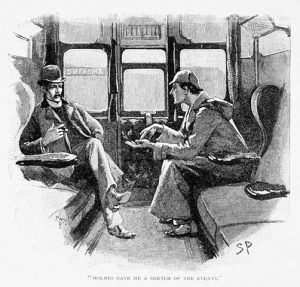

‘Well, Watson, what do YOU make of it?’ Holmes held the light blue notebook that I had just passed to him up to the light of the window, better to get a good look. ‘Your medical practice seems to be a magnet for the confused and bewildered at the moment!’ I had found Holmes in excellent spirits, having spent the morning perusing the columns of the dailies, and just in the mood for a little deductive exercise.

‘Well, Holmes,’ I replied, very pleased that I had brought something of interest to the great man. ‘I can see that it is a notebook of some kind. It is light blue with strange mottled orangey marks on it. The paper is fine, slightly cream in colour with watermarks. Undoubtedly it is encased in the finest English calf. That it is expensive and probably manufactured by one of our famous publishing houses such as the Cambridge University Press is obvious and no surprise to me having seen its owner who appeared to be a man of taste and education, even in his febrile state. It has nothing in it save the Latin inscription. If I may make so bold, Holmes, I suggest an immediate advertisement in the personal columns of the Times suggesting that the owner come here tonight at 6.30 to collect it whereupon we shall quiz him and get to the bottom of this perplexing matter. Have I missed anything?’

‘Everything of interest and importance, dear chap! Don’t look so miffed – you have done as well as anyone. However, what about the leather? Sniff it. It smells of a barnyard, does it not? Of chickens and geese and yet there is also the tinge of heather and tree bark about it. And what do you make of the orangey marks bursting out onto the light blue? Both these things suggest it is leather of a particular kind – Elk, probably Asian, although the breed has been established in Argentina of late. I am thinking of writing a small treatise on leathers which would be of value to Scotland Yard in securing convictions. But I digress…You see, Elk leather is notorious in being difficult to successfully dye – the orange patches cannot be completely hidden by our present methods of colouring. Hence the look of the book. It was not, I suggest, made here but probably in Hong Kong as they have the capability which China does not and a thriving trade in Elk, both for leather and also in antler velvet which is much prized as a medical treatment for gout and other complaints – you should investigate it for your long-suffering patients, doctor! An introductory article in The Lancet might not go amiss! As to your suggestion that we advertise for the owner, I feel that this might alert the sinister forces at work here.’

‘You think there are dangerous criminals at the bottom of this?’

‘Of course, my dear Watson. Consider the consternation of your young visitor this morning. And look at the motto ‘Spectemur Agendo’. We are dealing with strange and fantastic forces here. We must proceed with great care.’

‘And so what do we do?’

‘I need to telegraph my brother, Mycroft. Then there will be nothing of value that we can do until tomorrow morning. I suggest an exhilarating walk in Regents Park followed by an excellent early dinner at Rules in Charing Cross. Come, let us enjoy the beautiful spring day! I have one or two items to impart before you present the facts of our recent adventure at The Copper Beeches to your adoring literary public.’

TO LONDON TOWN

The next morning I passed my practice over to my colleague, Dr Mann, something we both did frequently as it left us free to pursue other interests when necessary. I was feeling quite excited at the day in store.

I had barely arrived at 221B at about 8 am when Holmes ushered me out into a waiting cab which rattled away to Trafalgar Square, and then up to Piccadilly Circus. ‘Sorry to rush you about, my dear fellow, but I think we have not a moment to lose. Let me explain.’ The cab swung into Shaftesbury Avenue.

‘And Mycroft’s telegram?’ I asked before he could begin.

‘Yes, well, as you have probably guessed,’ – which I hadn’t, but did my best to look like I had – ‘my telegram to Mycroft was to seek news of the importers of leather to this country from Asia. Mycroft, as I said before, IS the British Government when it suits him and he has access to all import licenses. In particular I wanted to find out about Elk skin and, to cut a long story short, exactly who had the right not just to make products from it but, more importantly for our purposes, who had the rights to sell them.’

‘And?’

‘Well, in brief, it is made into many things that are sold, but the stockists of notebooks number six. One is in Dublin, one in Edinburgh, one in Manchester and the remainder in London. Of these I have discounted those outside the capital as well as stockists at Farringdon and Victoria as the neighbourhoods are probably too rough for the likes of the chap you had the pleasure of meeting yesterday. He seems a nervous sort of fellow and I cannot see him shopping in those insalubrious locations. The most likely retailer is the one we are about to investigate.’

We passed the Royal Academy of Arts on our right. I noticed that they were putting on an exhibition of painting and drawing inspired by our illustrious Queen and Empire. We stopped at the entrance to the beautiful Burlington Arcade where Holmes paid off the cab.

Wandering up, looking to left and right, Holmes, with a grin of satisfaction eventually said, ‘Well, here we are!’

We entered a most lovely small shop with curved glass windows and a display of leather and cloth-bound notebooks of all descriptions and colours. A small man, balding, with a heavily waxed moustache, stood behind the tiny counter and eyed us coldly. ‘Yes?’ he almost hissed.

‘Oh dear, Watson I fear we are not cut of the right cloth for this gentleman!’ said Holmes in a whisper.

When he chose, Holmes was capable of immense charm and he used every ounce of it here. ‘Good-day, my good sir. I must compliment you on your most beautiful shop. The fact is that, we were at Rules Restaurant last evening – do you know it? I should imagine that a gentleman like yourself would, indeed – when I found upon our table a most beautiful notebook bound in Asian Elk skin which had obviously been left by a previous diner.’

The man behind the counter looked down his nose – ‘petit register de poche, I think you mean –’

‘I found the man’s pretensions almost intolerable but Holmes carried on as if charmed. ‘Of course, a most exquisite petit register de poche. Well, there is only one place where this beautiful item could have been purchased and that is here. I am most keen to return it to the owner and I wondered if you would be kind enough to let me have the address? Perhaps you could consult your sales ledger?’

‘Now look here, you meddlesome busybody – yer face is familiar, do I knows you?’ The man’s accent had slipped now and he came true, talking with a distinct lilt from the East End. He looked from one of us to the other. ‘Yes, and you,’ he said looking at me. ‘I knows you, too. You are that pair wot’s always in the papers. Who is it? Blimey, I’ve got it – the famous Sherlock ‘olmes and Dr Watson. You are welcome, sirs, both of you! Why didn’t you say who you was? He rushed out and shook Holmes by the hand. ‘You ‘elped a mate of mine when he was in trouble, Mr ‘olmes. He was up for murder and you got ‘im off. Johnston Bull. ’

‘Well, I managed to prove he was robbing the Greystone Bank in Bermondsey at the time of the supposed murder, if I remember, and he got 10 years,’ said Holmes smiling, ‘but I suppose that is better than the rope and many would regard such a fate as ‘getting off’! How is Johnston Bull?’

‘Due out any time now, Sir? And mighty grateful to you! I am sorry to have been so snooty, gentlemen, but you won’t believe the riff raff we gets in ‘ere. Now, what can I do for the famous Mr ‘olmes and Dr Watson?’

Holmes explained that we needed the address of the buyer of the pale blue notebook which he produced.

‘Well, sir, I don’t want to knows why you wants it, but the fact that you do is good enough for me. Now, I cannot actually give you the address – against the law you see – but I can quite easily leave my purchase book open on the counter at …’ he shuffled through the pages … ‘exactly THIS page whilst I nip into the back to check an item of stock. I can do that, can’t I? And I shall be gone a couple of minutes’. His eyes twinkled and Holmes smiled back. The charm was on the other foot now and I too stood enjoying the scene with a huge grin on my face. ‘And if, when I return, you’s both gone, well, there we are. Nuffink to do with me, is it?’

With that, our newest fan nipped into the back room and out of the shop. As he went we could just hear, ‘And wait ‘till I tells old Johnston Bull how I ‘elped the great Sherlock ‘olmes. Blimey! Ho-ho!’

LILY CARDSTONE

‘Oh, Mr Holmes, Dr Watson, it is indeed my dear brother’s notebook. Oh, my dear brother, he is all I have left now…now that mother has gone…far too early, far too early…’ The young lady half fainted as I helped her onto an elegant chaise longue and pulled the bell-rope for the morning maid.

The lady recovered quickly as her servant produced a glass of water. ‘I am so sorry, gentlemen. I am in a state of utmost anxiety regarding my poor brother. Oh dear. Oh dear!’

Holmes and I found ourselves in a most elegant detached villa, in East Cheam, a 35 minute train ride from Victoria and the address we had so memorably found in the register of the shop in Burlington Arcade.

‘I always find it is best to begin at the beginning, Miss Lily Cardstone – for such is your name, I believe. Please tell us in your own time of your worries. Leave nothing out as often the smallest details can be infinitely revealing.’ I was always amazed at Homes’ ability to charm and calm and the effect of his words along with a warm smile appeared to have the desired effect.

‘Well, gentlemen, well…’ Miss Cardstone began. ‘It all began to go wrong last summer. My dear brother, John, and I lived here with my Mamma and we were very happy until it became clear that Mamma was beginning to forget things and became very careless. Indeed, she actually injured herself with the fire coals and almost died one day when we were both in the garden. That was that. John and I both realized that, although physically very healthy, it was imperative that we found Mamma 24 hour nursing care.’

‘And you did?’ asked Holmes.

‘Yes, Mr Holmes. That was when we discovered the East Cheam Retirement Home. Oh, I would do anything not to have heard of that hideous place!’

‘Was it not comfortable? Was it not well staffed?’ I gently asked.

‘Oh, indeed, Dr Watson, it was both of those things. Our first impressions were very favourable. It was set in beautiful grounds and Mamma was given her own elegant room. John and I thought ourselves VERY fortunate, until…’

‘Until?’ I prompted.

‘Until, until dear Mamma started to go rapidly downhill. Within a few months she went from ‘ruling the roost’ as she was always want to do, to a pathetic wreck with a parched, stretched face. She suffered from severe stomach cramps. Dr Halstrom of the home said it was a rare case of extremely rapid dementia. We watched helplessly as she grew weaker and then she just gave up the will to exist. We buried her two months ago.’

Holmes lifted his eyebrows to me and I quietly muttered ‘arsenic poisoning’. The effect on Lily Cardstone was electric. ‘That was exactly what my dear brother said and he said it direct to Dr Halstrom for he has a temper and cares not for his welfare when he is roused! Oh, my darling silly brother. Now he is in hiding for he fears for his life! Mr Holmes, he is convinced that something is terribly amiss at East Cheam Retirement Home and he thinks our dear mother, being a very inquisitive and brave lady, found out about it and that is why she was killed.’

‘What were your Mamma’s hobbies, Miss Cardstone?’

‘Hobbies, Mr Holmes? What a strange question! She liked the usual things – she liked to walk in the countryside, and to read, especially Mr Dickens. She was a great fan and was very fond of ‘David Copperfield’. Apart from writing to my brother and me twice or three times week, that was how she spent her time mostly.’

I knew Holmes well and no-one but I would have noticed the tell-tale brightening of the eyes and the almost imperceptible narrowing of his nostrils that told me he was intensely interested in Lily Cardstone’s comments. He sounded nonchalant as he said: ‘she liked to write letters, did she? And did these letters grow increasingly rare as her condition deteriorated?’

‘Why, yes, Mr Holmes. Towards the end of her life her writing grew scrawnier and the period between the letters themselves increased. In the end we received no letter from her for about a fortnight and John and I knew that something terrible was amiss.’

‘Have you the letters?’ Holmes was abrupt almost to the point of rudeness as he was wont to be when getting to the nub of any matter.

Lily Cardstone rose up a little shakily and went to a redwood bureau by the window. ‘Here they are, Mr Holmes,’ she said, handing over a small batch of letters tied with a red ribbon.

‘No sealing wax, I see’ muttered Holmes, almost to himself.

‘Indeed not, Mr Holmes’, said Lily Cardstone. ‘My dear Mamma was fond of being what she called ‘a modern woman’. She laughed. ‘Dear John and I always gently ribbed her about it – she kept up with all the latest trends, including the new-fangled way of sealing letters by wetting the glue on the envelope and pressing it down. She also believed that women had a perfect right to drive cars and to vote. Oh, my dear Mamma – she was born a little too early, I think!’

‘I will keep these, if you do not mind’ said Holmes. ‘Now, let us talk about your brother. How long is it since you have seen him?’

Lily Cardstone dabbed her eyes with a silk handkerchief. ‘A few days ago I actually got my brother John’s agreement to see Dr Watson for he was in dire need of medical care. I have seen your image in the paper, you see, Dr Watson, and also read all of your adventures with Mr Holmes in the Strand Magazine. John and I used to read them to each other and to Mamma. They are just wonderful! So we felt a bit of a connection, you see. I suggested to him that he should consult you and after this seek to engage the services of the only man in England capable of getting to the bottom of this affair – your friend, the great Sherlock Holmes. But, as you now know, his nerves got the better of him and he ran from your surgery. I know because he came back here briefly to change clothes. He said he had found a safe bolt-hole and that he would go there and I was not to worry. And now he is gone again.’ Tears were flowing readily now.

‘Where has he gone?’ I asked softly.

It was Holmes who replied: ‘He has gone where no one will know him, has he not? I suspect he is hiding amongst the vendors and sailors at the docks. When I came in I passed your maid with a bundle of men’s dirty clothes. They were stained with the reddish-brown mud of the filthy Thames and the smell was unmistakable.’

‘But Holmes,’ I muttered. ‘The East End is huge and very dangerous. He could be absolutely anywhere. How can we possibly locate John without help?’

‘But, Watson, we shall have help. Think a second! Who is it that is coming out of prison as we speak? And who is it that knows the most dangerous places in the East End like the lines on his face? And who is it that owes me a favour?’

‘Why, Johnston Bull,’ I realized with a grin. ‘Johnston Bull’.

‘Precisely, my dear chap, precisely!’

MY FRAIL UNCLE HOLMES

It was just after 10 the next morning when Holmes said: ‘Now, you’ve got the story clear, I trust?’ as the very expensively-rented coach and horse clattered along the country road towards East Cheam Retirement Home.

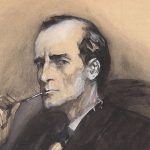

I looked at the frail, elderly man beside me. I had often had cause to marvel at Holmes’ ability to take on new personas but his time I swear even I would not recognize him if I passed him in the street. Gone was the sharp aquiline nose, the piercing eyes and the look of mastery he often evoked. Instead was a frail old man of about 80 years, sad and slightly delirious. The only tell-tale sign of Homes to me was the slight twitching of the nose and cheeks that I had come to expect when he was closing in on the scent, when the ‘Game was Afoot’ and rapidly drawing to a conclusion.

‘Yes, Holmes, you are my frail uncle in need of somewhere safe to stay. I have, as you instructed, confirmed by telegram with Dr Halstrom that we shall make a visit today. I have further agreed a colossal amount of money for your weekly care if we choose to engage the services of the good doctor and his Retirement Home.’

‘Excellent. I have instructed Inspector Lestrade and his team to wait hidden in the gardens until the signal is given for action. I have also asked Johnston Bull to bring a few of his boys along as I fear there may well be trouble.’

‘How will I know when to act? What will the signal be, Holmes?’

‘No idea, Watson, but I suspect there will come a time when all hell will break loose. And Watson…’

‘Yes, Holmes?’

‘I aim to give you and the doctor the slip as we are shown the premises. Remember to give me as long as you can when I go missing. Explain to Dr Halstrom that I am extremely confused sometimes, often go off missing for a few minutes and will probably come back when I am ready. If that fails to hold him up from raising the alarm, employ plan B.’

‘Which is?’

‘Hit him’.

DR HALSTROM

Dr Halstrom was charm itself. He welcomed us along with his staff of about ten who all lined up in a row to be introduced to my ‘uncle’ and myself. We were ushered inside and quickly upstairs which seemed a trifle brisk to me. Halstrom led us into a finely appointed room and said ‘I trust your dear, dear uncle will have everything he needs here. If not, he only has to ask me.’

‘I am sure he will be fine, doctor. Isn’t that so, dear uncle?’

I turned around but Holmes had vanished. ‘Oh, such a scatterbrain!’ I said. ‘I am sure he will be back soon!’

The doctor’s face turned white and twitchy with anger. ‘I do not allow my patients to wander off at will. It is far too dangerous! I must summon the staff to find him immediately!’

Doctor Halstrom reached out for the bell-rope. I had no alternative but to employ plan B. The doctor collapsed on the floor and I held onto my bloodied hand, gritting my teeth in an effort not to make any sound. One minute passed, then another.

THE FIGHT

It was a faint sound at first – a sort of gurgling and glugging. Then I heard some human voices from what seemed below me in the garden. They didn’t sound too happy. A shot rang out, followed by another. I looked out of the window and saw an amazing sight. There, running from the house and seemingly after a group of eight very dirty ruffians, brandishing a gun was an old man of about 80 years old. Only his agile and athletic stance showed that it was Holmes. Towards them were running another group of about five men headed by the huge figure of Johnston Bull. As the groups collided, Johnston Bull swatted one, then another of the ruffians with a huge grin on his face and as easily as if they were flies. ‘There’s one for you, Mr ‘olmes and …’ wallop ‘…here’s another for you Mr ‘olmes’. He was obviously having the time of his life. Beside him, completely rejuvenated by the turn of events, was his unlikely ally and new best friend, John Cardstone. Slowly, though, the ground they were standing on became a wet mess as more and more water poured from what must have been nearby manholes. Soon there was a mass wrestling match in a sea of mud and it was very difficult to work out who was who.

I rushed down to help, drawing my army revolver from inside my coat as I did so. Standing just clear of the mayhem was Inspector Lestrade and his men, also with guns in hand and handcuffs at the ready. Gradually, with the help of myself, John and Johnston Bull, each of the eight ruffians was identified, dragged kicking and screaming from the mud and brook to book.

Then the air was rent with a mad, agonized cry. Walking unsteadily from the house was the figure of Dr Halstrom. He looked at Holmes, now about ten feet in front of him. ‘I shall go, but so shall you, you meddlesome nobody!’ he shouted, bringing his gun up to chest height. Take that!’ He fired but, as he did so, a huge gush of water erupted from a manhole; he tottered for a moment, and then fell on his back in the mud. A police constable was on him in an instant and he was dragged to the waiting police van, a broken man now, bent and frail, offering no resistance.

HOLMES EXPLAINS

The next day witnessed a happy late morning meeting in 221B. Present were Holmes, myself, Inspector Lestrade, along with Lily and John Cardstone. Mrs Hudson left us to fetch coffee.

Holmes began. ‘It became obvious to me that your assessment of the situation must have been correct, Miss Cardstone. Your dear mother had indeed found out that something was badly amiss at the Home. Tragically, her bravery caused her death.’

‘If only I had been braver myself, I could have helped sort it all out!’ said John Cardstone. ‘But it needed your genius, Mr Holmes – and yours also, Dr Watson – to bring matters to a conclusion.’ I must say I felt tickled pink to be so complimented, although my task had been merely to follow instructions. John continued, ‘Mr Holmes, I know that you and Dr Watson have established that my dear mother was poisoned. I cannot, though, for the life of me work out how the arsenic was administered – my dear Mamma was sharp as a stick and would have smelt and checked her food. Where was it? In her soup? In her nightly cocoa?’

‘No, John!’ Holmes reached across to his writing desk and took out a pile of letters. ‘It was in – or more accurately ON these.’ He held up the letters. ‘It was a work of genius – almost. It didn’t take Dr Halstrom long to see that your Mamma liked nothing better than to write to your sister and yourself. Your Mamma was a private woman and insisted that she alone lick the envelopes and seal them down BEFORE letting them get collected for the postman. Dr Halstrom simply coated the glue on the envelopes with a thin coating of arsenic. I have had these letters analyzed by our forensic friends at Scotland Yard. The results will put a rope around the neck of a doctor who did just the opposite of what doctors are supposed to do – he killed rather than cured.’

‘Surely, Mr Holmes,’ said John, ‘surely she would have detected the taste of arsenic on the letters, would she not?’

‘Why, what does the glue on letters taste like, John?’

‘Well, whenever I have had occasion to lick a letter it tastes pretty disgusting’.

‘Precisely, the glue on even the finest stationery, which your Mamma would have used, is made of fish heads and skin and god knows what else. Arsenic tastes slightly sweet and metallic – a small amount, probably applied with a brush, would have been undetectable.’

This talk of her mother was all too much for Lily who let out a sob while John moved over to comfort her. ‘But why, Mr Holmes?’ she asked. ‘What was so important that such a man would consider murder? What on earth could justify such a thing? Do you think others were murdered apart from my mother? What was it all for?’

Holmes loved his theatrics and had no intention of spoiling his fun this morning. He possessed a large streak of vanity and was quite aware of the fact, regarding it as a most natural corollary of genius. He was going to take his time explaining things. That it seemed to me totally inappropriate to ‘have fun’ at such a time or ‘to play to the gallery’ would not have occurred to him. He knew all too well that the Cardstones and I, if not Inspector Lestrade who presumably knew everything, were itching to find out exactly what had gone on but he feigned nonchalance and sipped a cup of coffee. It fell to me to ask the question everyone was thinking: ‘What, exactly was going on there, and what did you do when you vanished, Holmes?’

Holmes and Lestrade exchanged amused glances. ‘To answer your question, Watson, in reverse order. What did I do? I went to the ground floor and turned on all the taps. Well, I say taps but they were more industrial gushers. I was not at all surprised to find them. It was obvious to me that Halstrom’s reluctance to let us stay on the ground floor meant that he was afraid we would find something out. I heard the faintest of sounds coming from the basement and an infrequent but detectable tremor. There was only one obvious course of action – I decided to flood out whoever was down there.’

‘What WAS going on in the basement?’

It was Lestrade who replied – ‘Oh, the manufacture and refining of all sorts of drugs and illicit substances. Drilling, too, which explains the vast amounts of water needed: exactly what for we shall undoubtedly find out at the trial – maybe gold as there have been rumors of great wealth lying under the soil thereabouts for generations. Anyway, what better cover than a Retirement Home where people could be kept permanently befuddled and, if necessary, I am sorry to say, got rid of quickly as became necessary with your dear Mamma, Miss Cardstone? As to other victims, I have applied to the authorities for exhumations of seven other persons who have died at the home in the last three months. I fear there may be even more shocks to come.’

‘Yes, the whole operation was a massive one’, continued Holmes. ‘It must have cost a king’s ransom to fund. I fear, however, that we have arrested the employees but not the boss. It has Moriarty’s prints all over it but he is far too smart to be anywhere nearby.’

‘I have one last question,’ I said. ‘What was the significance of the motto in John’s notebook – what was it ‘Spectemur Agendo’?

‘Oh, that,’ said John sheepishly. ‘That was just my school motto: ‘Let us be judged by our actions’. I wrote it to keep up my courage which I am afraid I lost in spectacular fashion before getting it back at the last. I have to thank Johnston Bull for that as it was he who found me in my disgusting hide-away adjoining the stinking Thames, and also made me see I had to fight back. He is not here this morning as he is engaged in some venture in the West End of London, the exact nature of which I am sure neither Mr Holmes nor Scotland Yard will want to investigate too closely, but he told me he needed to sort his bank out, by which I hope he means he is opening an account and nothing else!’

There was silence for a moment as Lestrade looked uncertainly at John and then at Holmes before all of us erupted into laughter.