Many see Charles Dickens as the world’s greatest novelist, and this includes some of his illustrious contemporaries such as Leo Tolstoy. His life proceeded almost as dramatically as his plots – his father was imprisoned for debt when he was 12 years old and yet, just over a decade later, he had become one of the most famous people on the planet and the world’s first literary superstar.

Charles Dickens was born in Mile End on the outskirts of Portsmouth on 7th February 1812, seven years after the Battle of Trafalgar and three years before the final defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo. It was a Friday, the same day as his ‘favourite child’, David Copperfield, was born, and a day that was always special to him. His father, John, who worked for the Naval Pay Office, was a friendly and gregarious chap, good-looking by all accounts, and always had his brain attuned to what we would today call ‘upward mobility’. Charles’ Mother, Elizabeth, was 23, and shared her husband’s taste for ‘society’ – indeed; she is reported to have attended a ball on the eve of the birth. Charles already had a sister of eighteen months, Fanny.

Dickens’ birthplace, Portsmouth

Dickens’ birthplace, Portsmouth

THROWN INTO A BLACKING FACTORY

At 12 years old, his father having been imprisoned for debt, Charles was sent to Warren’s Blacking Factory where his dreams of becoming a gentlemen seemed lost for ever amongst the rats flooding into Hungerford Stairs from the adjacent River Thames but, even more importantly, in his young head, for he cried at the unfathomable shame and pain of it all. He was a very sensitive boy and was most upset when he gained the nickname ‘the little gentleman’ from his young workmates. He had one good friend, however, called Fagin, though why this lad’s name ended up appended to the premier villain in Oliver Twist, is a mystery. Maybe it is because not all of Fagin is villainous and this young man represented the kindly side, the side that shied away from the pure evil of Sikes.

Dickens in despair in the Blacking Factory

Dickens in despair in the Blacking Factory

TO ROCHESTER

The Dickens family moved several times in the early years and, in April 1817, they were posted to Chatham which merges with the historic town of Rochester. Charles was five.

Chatham is not writ large in Dickens’s work. However, it does have the distinction of being the model for Mudfog which features in The Mudfog Papers, serialized in Bentley’s Miscellany when Dickens was 25 years old. This is a piece of youthful literary slapstick, maybe not as subtle as his later work but extremely funny. It follows the proceedings of ‘The Mudfog Society for the Advancement of Everything’, a parody of The British Society for the Advancement of Science which had been set up in 1831. Although this particular society has become extremely respected it was, at the time, just one of many which were set up by the high-minded Victorians for the advancement of just-about-everything and it was a target that the youthful high spirits of Dickens could not resist.

In literary terms, Rochester – a little way along the very same street as Chatham – is the famous town to which the Pickwick Club came for its first adventure. Dickens was 24 and, before the book – published in monthly parts – was anywhere near finished, he was a major and permanent star in the literary firmament.

Dickens and family at home in Rochester

Dickens and family at home in Rochester

‘Pickwick’ was actually born of tragedy in that the original and brilliant illustrator, Robert Seymour, blew his brains out after a few episodes. ‘Sketches By Boz’, a previous literary attempt, had been enough of a success to persuade Chapman and Hall, the publishers, that the young Charles might possibly contribute to the project. The vision was, initially, illustrations about sporting life with explanatory words: upon Seymour’s death, Dickens succeeded in having this reversed – henceforth his writing would be the main feature and the drawings would back up his text. Also, Dickens knew next to nothing about sport: Dickens is rarely inadvertently funny, but his lack of understanding of the rules of cricket, in a scene at Dingley Dell, will bring a chuckle to lovers of the game. He didn’t know his square cut from his fine leg.

The Pickwick Papers was initially only a very minor success. At first, monthly sales struggled to reach 500. When Dickens introduced Sam Weller as Mr Pickwick’s worldly-savvy but golden-hearted manservant, sales shot up to the tens of thousands. There is almost no predicament, one feels, that the unworldly but kind Mr Pickwick can get himself into that the canny young Sam – aided by his father sometimes – cannot get him out of.

EASTGATE HOUSE

It was in his early life at Rochester and Chatham that Dickens studied some of the buildings that were to be immortalised in his greatest works. Eastgate House in the High Street is an example of a setting that Dickens used in more than one novel. A genuine school for girls in Dickens’ time, it serves as the Westgate Seminary for Young Ladies, scene of Mr Pickwick’s comic misadventures in The Pickwick Papers. Rosa also attends Miss Twinkleton’s school for young ladies, an identical building but transferred to Bury St Edmunds, in The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Here: ‘Rosa soon made the discovery that Miss Twinkleton didn’t read fairly. She cut the love-scenes, interpolated passages in praise of female celibacy, and was guilty of other pious frauds’.

Eastgate House

Eastgate House

MISS HAVISHAM’S HOUSE

An even more famous building is Satis House, Home of Miss Havisham in Great Expectations. It is also the last place Dickens was seen alive by the public three days before his death in 1870: the reason that he had come back to survey it is unknown, but maybe it held especial charms for him or maybe he was going to use it again in his last great, unfinished novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood.

Miss Havisham’s House, Rochester

Miss Havisham’s House, Rochester

If you carry on walking, Vines Park hoves into view. Pip takes this route on his way to see Miss Havisham for the last time in Great Expectations. He would probably have been thinking of all his past pain – the desperate, unrequited, love for Estella, who had been brought up by Miss Havisham to break men’s hearts. Maybe he was thinking of her cruel words: ‘Moths, and all sorts of ugly creatures hover about a lighted candle. Can the candle help it?’

Surely, too, he could have been wondering how he managed to keep his young sanity, on his most significant previous visit. The lady of the house, jilted on her wedding day, had resolved to keep everything in one room exactly as it was at twenty to nine that fateful morning, at the exact moment she received the unforgivable news of her lover’s desertion and treachery. Pip, a young and innocent boy, in love with a girl who seems to despise him, is introduced to the rot and decay of the wedding room, in a scene of horror enough to send a sensitive nature over the edge. Pip is talking:

‘The most prominent object was a long table with a tablecloth spread upon it, as if a feast had been in preparation when the house and the clocks all stopped together. An epergne or centerpiece of some kind was in the middle of this cloth; it was so heavily overhung with cobwebs that its form was quite indistinguishable; and, as I looked along the yellow expanse out of which I remember its seeming to grow, like a black fungus, I saw speckle-legged spiders with blotchy bodies running home to it, as if some circumstance of the greatest public importance had just transpired in the spider community…

“This,” said she, pointing to the long table with her stick, “is where I will be laid when I am dead. They shall come and look at me here.”’

Pip’s last visit does, in fact, end with Miss Havisham’s death. She catches her dress in the fire and dies of burns a short while later. She realizes that she has merely broken Pip’s heart, ruined Estella’s chances of happiness, and achieved nothing by her selfishness. She cries, “What have I done? What have I done?”

TO LONDON: THE MIGHTY THAMES

Citizens of the capital will tell you that, today, London is inhabited by two types of people – those who act as if it is the centre of the universe and those who know it is. Dickens subscribed to the latter view. London imbues most of his writing, and often he was fascinated by the dirt and squalor of it all:

‘It was a foggy day in London, and the fog was heavy and dark. Animate London, with smarting eyes and irritated lungs, was blinking, wheezing, and choking; inanimate London was a sooty spectre, divided in purpose between being visible and invisible, and so being wholly neither.’

Our Mutual Friend

Even the rain cannot wash the city clean:

‘In the country, the rain would have developed a thousand scents, and every drop would have had its bright association with some beautiful form of growth or life. In the city, it developed only foul stale smells, and was a sickly, lukewarm, dirt-stained wretched addition to the gutters.’

Little Dorrit

The mighty River Thames is often a metaphor for life itself in Dickens’s work. Rain, tears, rivers, fogs and mists, stagnant pools, the sea – all are omnipresent in his great novels. Thus we have the pure heaven-sent tears that young Paul Dombey cried when he himself was heaven-bound; the mighty ocean, over which Scrooge flies in A Christmas Carol, embracing ‘secrets as profound as death’; it is also at once the means of escape to a new life for the Micawbers in Australia and the ultimate arbiter for the flawed romantic hero, Steerforth, dying in a terrifying storm off Yarmouth after his fateful deeds in David Copperfield; Miss Havisham’s tears for a wasted and cruel life in Great Expectations – water, water everywhere. Except, that is, for the arch-villains: Murdstone, Ralph Nickleby, Squeers, Jonas Chuzzlewit, Scrooge in his unreformed state, Quilp, Mr Dombey, Uriah Heep, Fagin, at least partially as he does a good deal of quivering and tearful wailing in his condemned cell, and I think Dickens maintained a soft spot in a small corner of his heart for him – these men don’t cry. For Dickens, shedding tears is an act of redemption and some he did not wish to redeem.

THE STRAND

Dickens knew this area intimately both from when he was working at the blacking factory and from his travels to and from the House of Commons in his time as a newspaper reporter (which didn’t last long as he was to become far too famous for such a job as this). We can imagine, though, between here and Covent Garden, a poor little waif – ten years old in the fictional account, David Copperfield; twelve years in reality – eeking out his weekly pay for food and treats. He tells us that he quickly became a connoisseur of pudding: a shop near St Martin’s Church sold a very nice pudding, full of currants, but it was twice the price of a more bland but equally filling type – ‘flabby’ with currants placed a long way apart – from another shop in the Strand. Down by the present Embankment tube was a ‘miserable’ pub, ‘the Lion, or the Lion and something’, from which he could dine more expensively if he had the money. Here he might buy ‘a saveloy and a penny loaf’ or a ‘fourpenny plate of red beef’. One very special time, he went to an ‘alamode’ beef house in Drury Lane and asked for a ‘small plate’ of beef’ which he ate with some bread he had brought with him. The waiter had rarely seen anything so comical as this young ragamuffin mixing with well dressed ladies and gentlemen, no doubt all out to see a show, and he called his colleague over to watch. We can only imagine the burning shame of the little chap who was out on his own because his father was imprisoned for debt and who had had to earn his meager supper money rubbing shoulders with Mealy Potatoes. ‘I am a gentleman; yes I am, really …’

Charles Dickens/David Copperfield drank ale with meals, in the morning and all day as water was dangerous. On one special occasion, maybe he thinks his birthday, he went into a pub and asked for a glass of ‘very best’ ale. The landlady gave it to him, though probably somewhat watered down, bending down to give him a kiss and his money back at the same time.

The Adelphi Theatre is just up the road. Young David remembers wandering around here as it had tantalizing alleys and passageways. Later in life, Dickens would cooperate with his good friend, Wilkie Collins, to adapt the Christmas story No Thoroughfare and put it on at this theatre. It was an enormous success and ran for over 150 performances. It made a fortune. Did it make Dickens content? Silly question.

Also, at the time, this area was a good place to find lodgings. In David Copperfield Mrs Crupp gave David, his Aunt and Mr Dick an apartment here following Betsey Trotwood’s financial ‘ruin’ by unscrupulous persons who would soon be most satisfyingly undone by the lion-hearted, if occasionally shambolic, Mr Micawber. Aunt Betsey soon brings the landlady to heel by hilariously demonstrating who is in charge of the flat and her beloved ‘Trotwood’. She…’ struck such terror to the breast of Mrs Crupp, that she subsided into her own kitchen, under the impression that my aunt was mad.’

48 DOUGHTY STREET, LONDON

This was the pleasant and relatively expensive rented house in which Dickens lived following his first successes. He had married Catherine and used to venture out on his famous night walks from here where he would mull over possible plots and characters, returning as dawn broke to write down his thoughts in a torrent of energy. His wife, and anyone else around at the time, knew better than to get in his way.

Catherine Dickens

Catherine Dickens

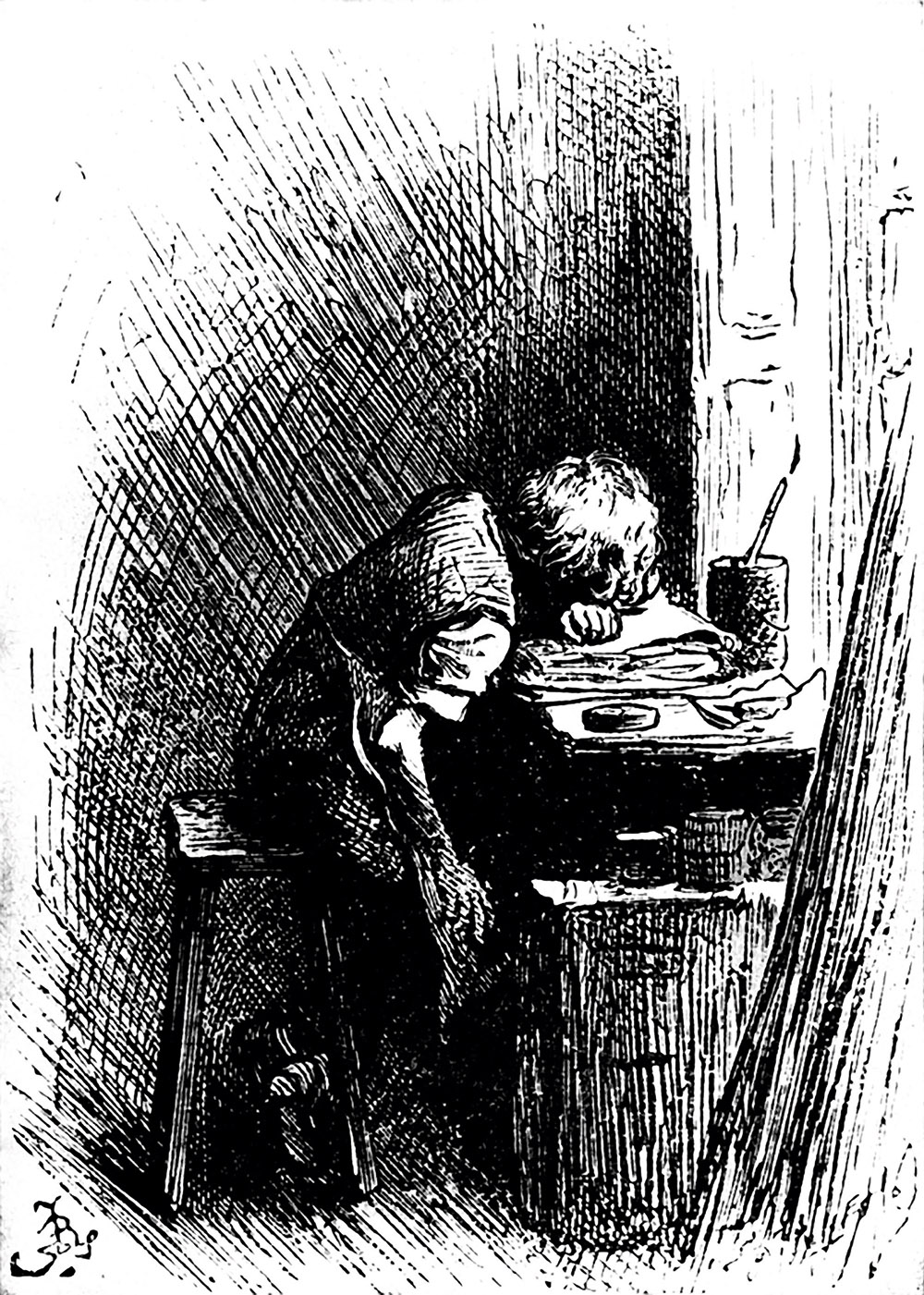

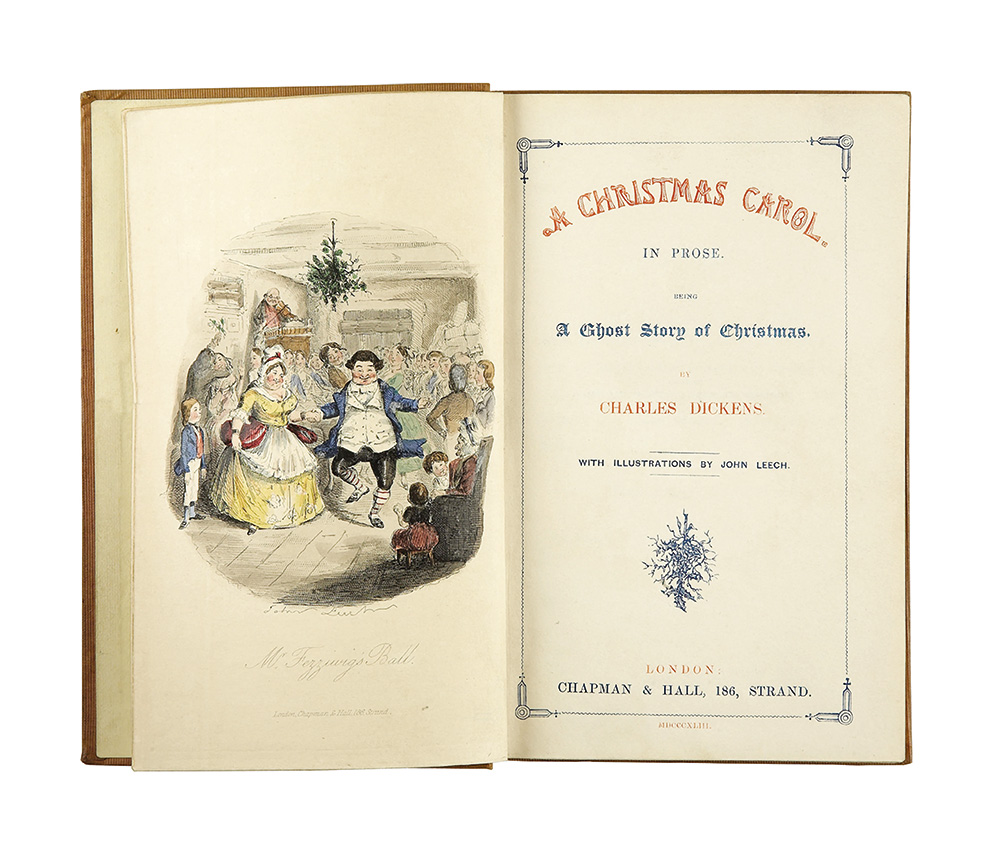

Dickens’s early life was rounded off with a work for which he will always be remembered – A Christmas Carol. He was just 31 when it came out to unprecedented and universal acclaim in 1843. This is a portrait of him in Doughty Street about that time by his good friend Daniel Maclise. It shows a young, confident individual looking up and out into the world. Were there any more mountains to conquer? Could he possibly go on to greater things? He most certainly could.

A Christmas Carol

A Christmas Carol

Just a little way up Wellington Street, off the Aldwych, is one of the most important addresses in literary London – you will see the Charles Dickens Café with a plaque on the wall above. These are the offices where Dickens supervised his hugely successful weekly magazines, Household Words (1850-59) and All the Year Round (1859-70). Charles Dickens Jnr continued the latter successfully until 1893. Dickens, world-famous and bursting with energy at the age of 38, decided to launch Household Words as a general magazine to show that, in all things, ‘there is Romance enough, if we will find it out’. Priced at only tuppence it came out every Wednesday beginning on 27th March 1850. Immediately, along with fiction and general pieces, it championed social reform and contributed to the reforms in the sewerage system following the ‘Great Stink’, when the business of the House of Commons was suspended. Dickens serialized Hard Times and A Child’s History of England in it, too, and he attracted some eminent writers, such as Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton, John Forster and Wilkie Collins to contribute to it. The most eminent female author of the day, George Eliot, declined as she was not too keen on the idea of weekly serialization.

COVENT GARDEN

This is Covent Garden. Dickens was known to take rooms in the Piazza here sometimes when his houses were not available for whatever reason. Tom and Ruth in Martin Chuzzlewit wander here early in summer mornings. They had both had a terrible time – Tom unjustly sacked by the pernicious hypocrite, Pecksniff, and Ruth humiliated when governess to what we might today call an uneducated and very rude ‘nouveau riche’ family with ideas way above their station. As a harbinger of vastly improved fortune for both of them just around the corner they have these lovely early morning strolls as regular as clockwork ‘snuffing up’ – what fantastic English! – the perfume of the fruits and flowers, pineapples and melons, veal stuffed but yet uncooked, ‘lusty snails and fine young curly leeches.’ David Copperfield buys flowers for Dora in the market here. I am reminded of two elderly sisters who told me whilst researching a book (When Schooldays were Fun, Halsgrove 2010) how they would get up really early on spring mornings in their country village and pick primroses. These would have to be ready for the early-morning train to Covent Garden. They received 1p a bunch for them. This would have been in the 1920s, but it is a charming story and it is nice to think that, mixing fact and fiction, David might well have bought flowers picked by their grandmothers.

Dickens tells us of a most bizarre scene he witnessed on one of his famous night walks. He had been walking all night, the sun was about to make an appearance and he sought a hot drink in a café in Covent Garden. In came a man in a snuff-coloured coat, shoes and a hat – nothing else as he could make out. This man had a very red face shaped like a horse. He ordered a pint of tea, a small loaf, a plate and a knife. Then, out of his hat he produced a very large cold meat pudding. This was placed on the plate and he proceeded to stab it, overhand, with the knife which was wiped on his sleeve. He then tore the pie apart with his hands and ate it all up. Dickens saw this twice. On the second occasion, the man asked the café-owner if he – the man with the hat – had a particularly red face. The owner replied, yes, indeed, his face was very red that morning. The man then confided that his mother had liked her drink and that he had stared at her hard in her coffin and the redness had transferred to him. Thereafter Dickens could not go into the café again.

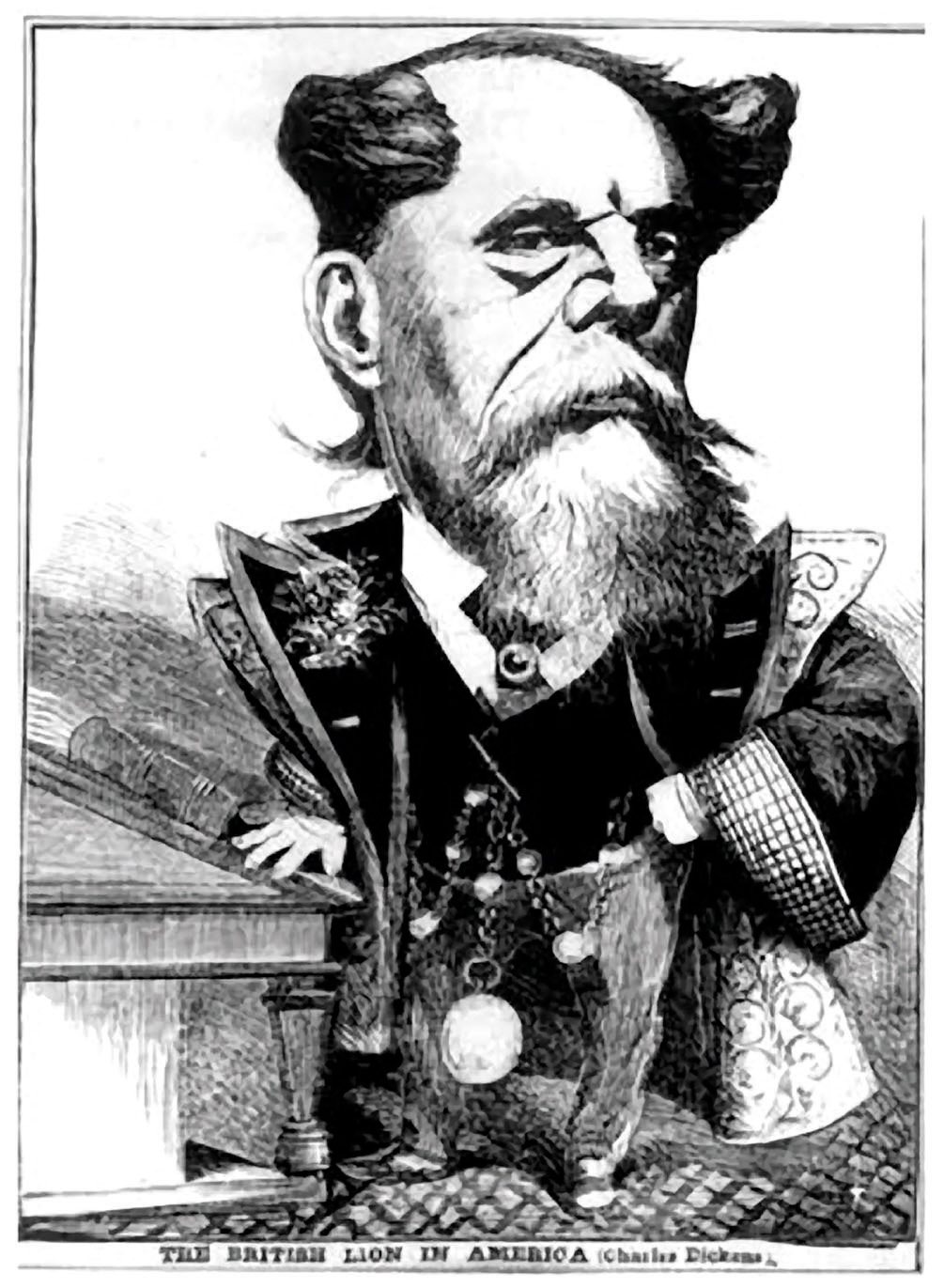

Dickens the literary lion, a contemporary cartoon

Dickens the literary lion, a contemporary cartoon

LINCOLN’S INN FIELDS

Head down Kingsway from Holborn Tube and take the first left into Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Dickens was at his best when angry and the interminable processes of the law were one thing that made him very angry indeed. Not that the rulers of the kingdom always minded. Sir Leicester Dedlock, one of the parties to the Jarndyce suit in Bleak House, could find nothing really wrong with an interminable Chancery suit. Indeed, being ‘a slow, expensive, British constitutional kind of thing,’ it was quite comforting, even if it did involve ‘an occasional delay of justice and a trifling amount of confusion’. It had been designed by his forefathers as an apex of human wisdom and any attacks on it by the lower classes would inevitably encourage revolution. So he was content to let it go on, being fleeced and deceived by his own solicitor, Tulkinghorn, all the while. Eventually, he lost his wife, too, the beautiful Lady Dedlock, who perished of despair and a broken heart on the grave of her former lover, Nemo, not far from where we are standing now.

Sir Christopher Wren’s St Pauls Cathedral, finished in 1711, is the backdrop to many of Dickens’ scenes. It signifies, generally, hope in the face of adversity and could be seen from virtually all over London. Today it must share the skyline with modern structures bearing names like ‘The Gherkin’ and ‘The Shard’.

Just along the river bank, a little inland, lies the Monument. In Martin Chuzzlewit, which Dickens himself thought his finest work altho’ extremely disappointing sales showed that the general public disagreed, we have an amazing description of the area of London around the Monument. This is where Todgers’ – accommodation for young gentlemen – existed:

The incomparable Mrs Gamp

The incomparable Mrs Gamp

‘You couldn’t walk about Todgers’ neighbourhood, as you could in any other neighbourhood. You groped your way for an hour through lanes and bye-ways, and courtyards, and passages; and you never once emerged upon anything that may reasonably be called a street. A kind of resigned distraction came over the stranger as he trod those devious mazes, and, giving himself up for lost, went in and out and round about and quietly turned back again when he came to a dead wall, or was stopped by an iron railing, and felt that the means of escape might possible present themselves in their own good time, but that to anticipate them was hopeless’.

You fell over pubs:

‘To tell of half the queer old taverns that had a drowsy existence near Todgers’, would fill a goodly book; while a second volume no less capacious might be devoted to an account of the quaint old guests who frequented their dimly lighted parlours.’

CITY

A little farther north is Smithfield. This is the location of Mr Jaggers’ office in Great Expectations. Young Pip has to come here and, as Mr Jaggers is not available, he goes for a walk to pass the time. ‘So I came into Smithfield; and the shameful place, being all asmear with filth and fat and blood and foam, seemed to stick to me. So I rubbed it off with all possible speed by turning into a street where I saw the great black dome of St Pauls…’ He carries on and is confronted with a ‘partially drunk’ minister of justice who tries to extort money from him by promising to show him the local gallows and the Debtors’ Door out of which will come, at eight next morning, four convicted felons sentenced ‘to be killed in a row’. Pip is sickened and gives him a shilling to make him go away.

The City

The City

This area – City, Barbican, Smithfield, Barts Hospital and down to the Old Bailey – held a special place in Dickens’ heart. Smithfield’s gruesome appeal is easy to fathom. It had always been a place of blood, torture and death. William Wallace was strung behind a horse and dragged here in 1305 to be hanged, drawn and quartered. Much more hanging and torture followed. In Dickens’ day, it was notorious as the scene of muggings, especially if you were not a local and your face did not ‘fit’. Then, of course, until 1855, cattle were slaughtered here, as young Pip, above, found out. In Oliver Twist, Oliver and Sikes pass through here on the way to rob the Maylie house and we are told that ‘the Ground was covered, nearly ankle deep, with filth and mire’. Smithfield is also mentioned in Barnaby Rudge and Nicholas Nickleby.

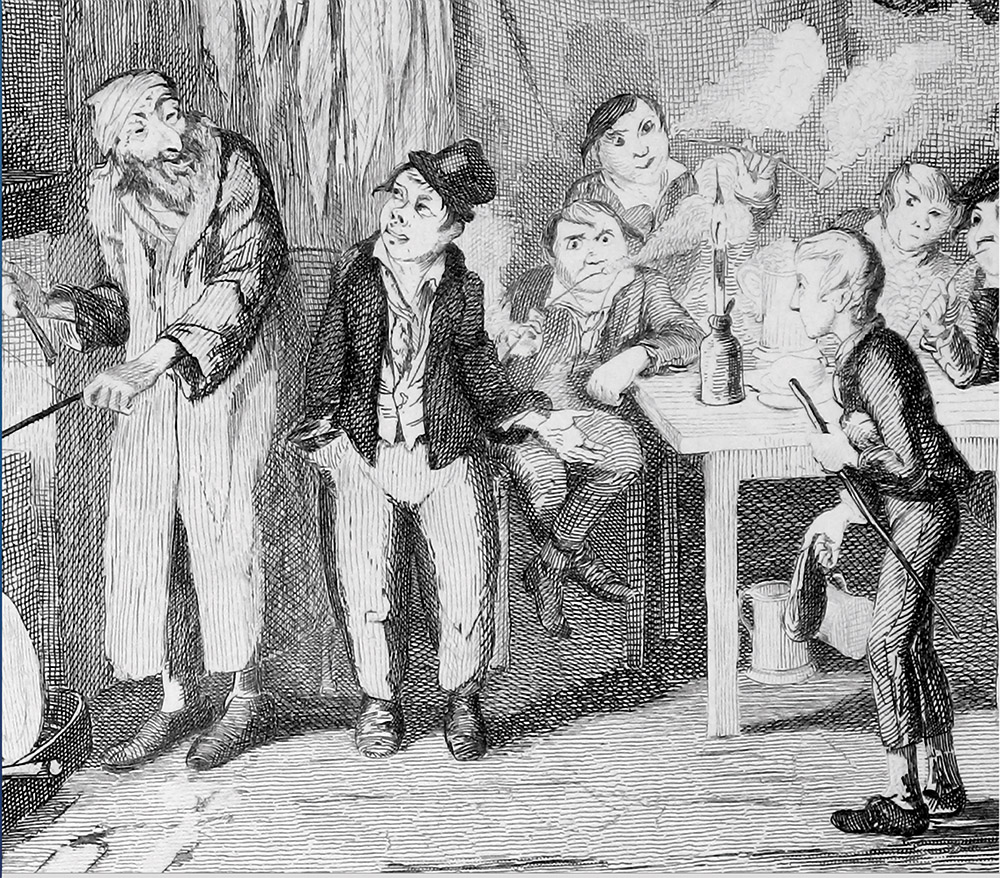

Oliver Twist is introduced to Fagin

Oliver Twist is introduced to Fagin

SOHO AND OXFORD STREET

If you walk through Soho, more or less parallel with Shaftesbury Avenue on the south side and Oxford Street on the north, you hit Dean Street. Turn left and, at the top, is Soho Square, always packed these days with folk eating and drinking as it is one of the very few oases of green in this part of the city. I remember, when I was working around here, that if you could secure a seat at lunchtime you felt as if you had won a small jackpot. Dickens places the home of Dr Manette and his daughter here in A Tale of Two Cities. It is also where Esther and Caddy Jellyby stroll in Bleak House. They are going to Turveydrop’s Dancing School to try, not for the first time, to break the news of Caddy’s engagement to her beloved Prince (that’s his name, not a royal title). Let us walk with them north from the Square, straight up Dean Street until the mighty bustle of Oxford Street cuts across it. Immediately opposite is Newman Street and it is here, in his Dancing School, we meet that incorrigible old rogue and Master of Deportment, Mr Turveydrop. Esther is presented:

‘Charmed! Enchanted!’ said Mr Turveydrop, rising with his high-shouldered bow. ‘Permit me!’ handling chairs. ‘Be seated!’ Kissing the tips of his left fingers. ‘Overjoyed!’ shutting his eyes and rolling. ‘My little retreat is made a paradise!’ Re-composing himself on the sofa, like the second gentleman in Europe.’

There follows one of Dickens’ many masterclasses in comic writing as Mr Turveydrop is eventually prevailed upon to accept the engagement of his son, Prince, and Caddy.

Oxford Street, London (photo by Daniel Tink)

Oxford Street, London (photo by Daniel Tink)

BACK TO ROCHESTER

Dickens set his great novels in many places – Yorkshire, Southsea, Guildford, Norwich and France amongst others, but there was only one place to which he would finally return.

When he was a small boy living in Rochester, Dickens would often walk past a house that seemed to him an enormous palace. On remarking of it to his father he was told that if, and only if, he worked very hard, then he may be able to buy it for himself in later life. He never forgot this and duly did buy it. It is where he died. Before this, though, he loved to have weekend guests stay and would find any excuse to put on a ‘play’. It has often been said that Dickens’ literary talent kept a great actor from the stage. Certainly, he was always fascinated by the theatre and loved to take a leading role in plays and entertainments of all sorts – we have Mamie Dickens’ warm accounts of life at Gads Hill Place where, especially when he had guests and at Christmas, all manner of entertainments would be put on. He also enthusiastically took part in semi-professional productions, which is how he came to meet Ellen Ternan. And, of course, he had the very greatest professional success when he wrote for the stage – witness No Thoroughfare, co-written with his great friend, Wilkie Collins, which wowed them at the Adelphi in the Strand.

The World of Charles Dickens by Stephen Browning is published by Halsgrove at £16.99